Environment

Comprising a 660,352-acre wedge of land on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada, Calaveras is a diversified landscape with a wide range of natural resources and climatic conditions. The narrow eastern border lies in rugged alpine terrain 7,200 feet above sea level, where total snowfall approaches 50 feet in an average winter. The broader western border is drawn across the low-lying Sierra foothills adjacent to the great Central Valley, a fallow but hot and rainless land from May until storms begin in the fall. The ragged lines of the flanks follow the northeasterly trend of two major tributaries of the San Joaquin River, the Mokelumne on the north and the Stanislaus on the south, almost to their sources high in the mountains. Those rivers supply much of the water for farmers in the San Joaquin Valley, and for industrial and domestic users along the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay. In between the county’s northern and southern borders is the Calaveras River, actually much smaller in recent geologic times than the ancient river system that once traversed the central Sierra. It still drains much of the county and provides the principal water resource for San Joaquin County communities and farms downstream.

Gold miners first gained access to the southern Sierra foothills by following the rivers upstream from the San Joaquin plains through the Bear Mountain Range, a north-south trending barrier the Calaveras River breached near Toyon Flat. Gold Rush overland routes evolved into major arteries—Highways 4, 12, and 26 today—connecting the supply centers in the Central Valley to the mining camps, once the county’s principal population centers. Now, new structures are sprouting along these transportation corridors all the way from Wallace and Copperopolis on the western boundary to neighboring Alpine County on the Sierra crest. Most of the newcomers, however, settle in the foothill towns and suburban developments, close to the Central Valley but still part of the Mother Lode. Angels Camp, the county’s largest town with an estimated 3,150 residents as of 2001, is growing about 2.3 percent a year, slightly faster than the county as a whole.(1)

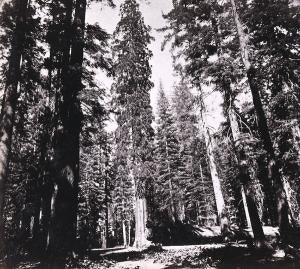

The varied life zones ranging from lower Sonoran to Canadian in this angular country support an abundance of wildlife, with many species endemic to the area, although some have been endangered by human and exotic plant intrusions over the past century. The forest canopy extends from the scattered digger pines and oaks at lower elevations through the foothills to the mixed pine, fir, and cedar forests in the higher elevations. The diversity of surface resources attracted the first humans to Calaveras shortly after the last ice age some 10,000-12,000 years ago. For thousands of years Native Americans lived quietly and successfully on the land, adapting to its rhythms and natural cycles, utilizing its animals and fibers, learning to drive game by setting fire to the grassy rangeland and the brushy understory of the upper slopes, moving higher and lower as the food supply and living conditions changed with the seasons, keeping population in tune with the resource base.(2) Environmental historians recognize the impact of early human changes on natural ecosystems, correcting distorted pioneer portrayals of starving “diggers” as well as romantic views that fostered an idyllic image of Indians living in unchanging “harmony” with the land.(3) But the pace of change accelerated rapidly with the coming of Europeans, and escalated explosively with the arrival of Americans during the Gold Rush.

Beneath the placid Calaveras foothills, the Mother Lode angles across the western part of the county in a northwestern-southeastern direction. This deep and tectonically significant structure of faulting and mineralization testifies to the long and violent geological history of the Sierra Nevada range. A relatively narrow zone stretching more than one hundred miles from Mariposa to El Dorado Counties, the Mother Lode is sliced by numerous faults, many of which were mineralized with gold-bearing quartz veins. The subsequent deep geologic erosion of the Sierra Nevada freed the gold from the grip of quartz, and concentrated it in many placer deposits in the rivers and streams. The Gold Rush followed directly from the discovery of nuggets in these deposits.

Ronald H. Limbaugh and Willard P. Fuller Jr., Calaveras Gold, University of Nevada Press, 2002, pp. 1-4

Footnotes

1. U.S. Census Bureau; California statistical Abstract, table B4 (Sacramento: California Department of finance, 2001)

2. Eugene L. Controtto, Miwok Means people: The Life and Fate of the Native Inhabitants of the California Gold Rush Country (Fresno: Valley Publishers, 1973), 8-9.

3. William Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (New Yoork: Hill and Wang, 1983), 9-14, 48-51; Cronon, “Under an Open Sky: Rethinking American’s Western past,” in Kennecot Journey: The Paths Out of Town, ed. W. Cronon, G. Miles, and J. Gitlin (New York: W.W. Norton, 1992), 28-51; Lary M. Dilsaver and William C. Tweed, Challenge of the Big Trees of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks (Three Rivers, Calif: Sequoia Naturla History Association, 1990), 22-24; M Kat Anderson, Michael G. Barbour, and Valerie Whitworth, “A world of Balance and Plenty: Land Plants, Animals, and Humans in a Pre-European California,” California History 76 (summer and fall 1997): 14-16, 33-39.