Mokelumne Hill and Campo Seco Canal

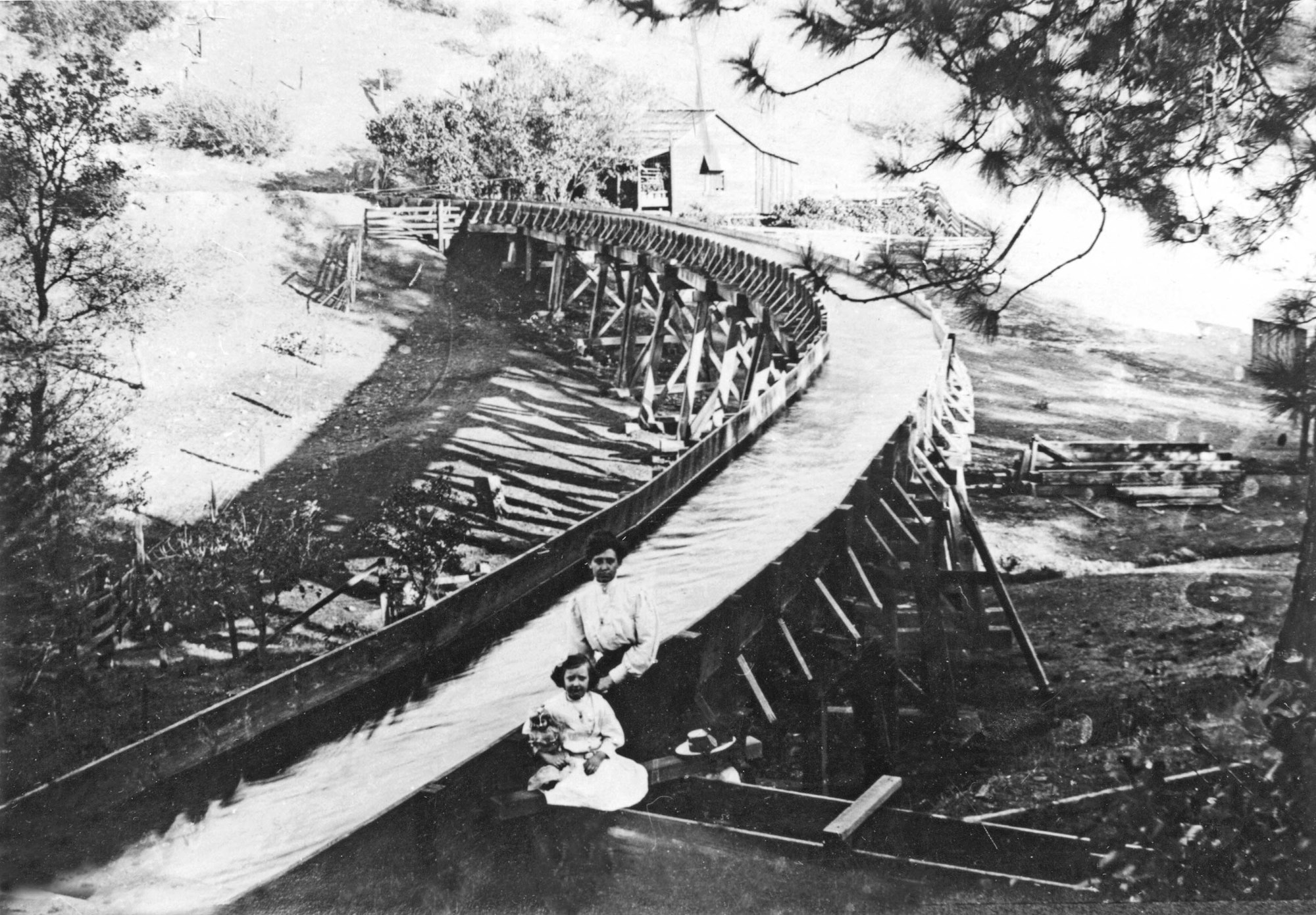

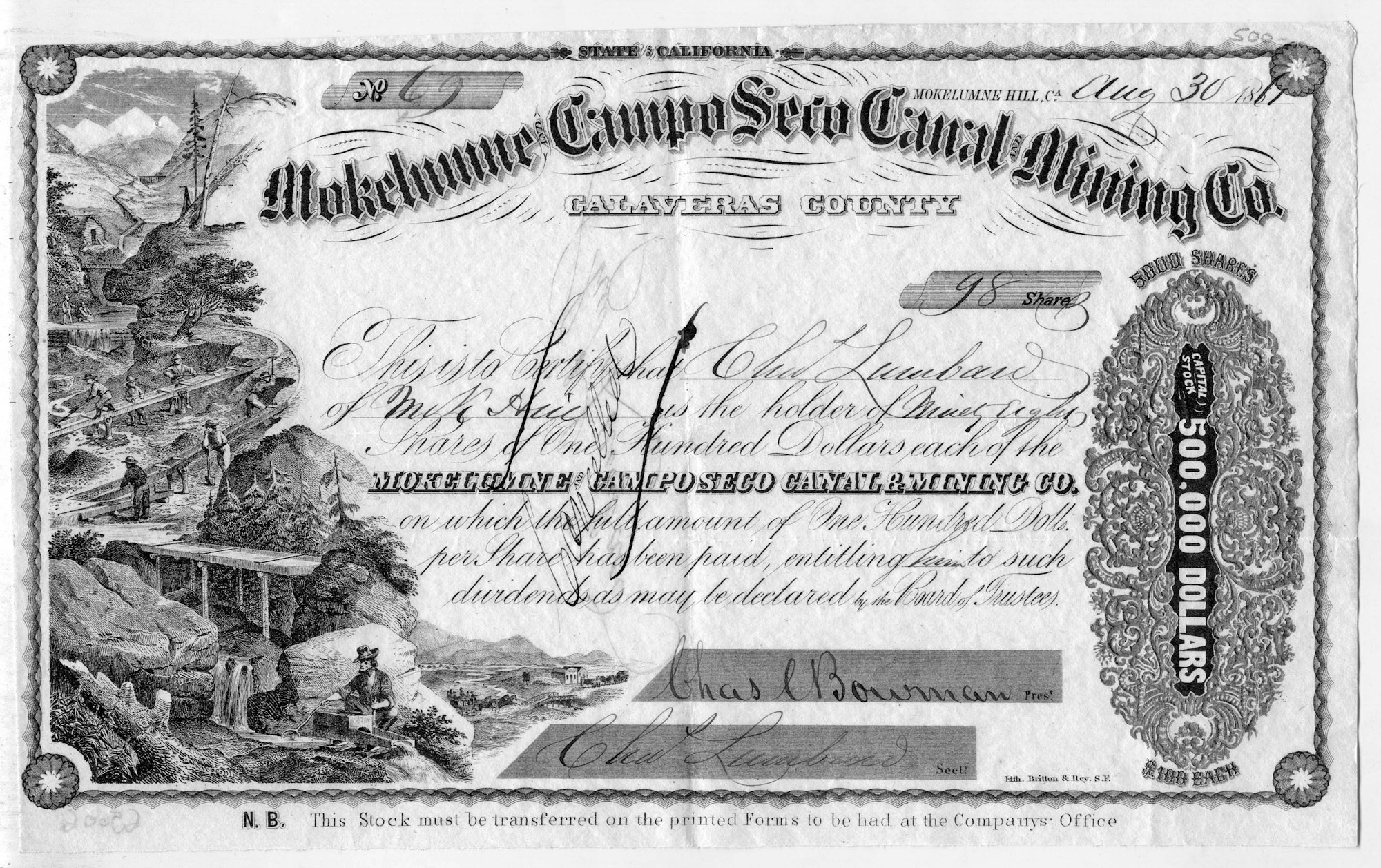

The Mokelumne Hill and Campo Seco Canal and Mining Company, formed in Mokelumne Hill on November 16, 1852, was created by a company of men to work the immense gravel deposits in the vicinity of Mokelumne Hill and Chili Gulch. Their purpose was to construct a canal to convey the waters of the South Fork Mokelumne River to the mining and agricultural districts south and west, which would be used for “mining, mechanical, agricultural manufacturing and other purposes.’ Capital stock was $150,000, divided into 500 shares of $100°° each. The ditch, with a capacity of 1000 miner’s inches, was subsequently extended to Campo Seco, Camanche, and vicinities, a distance of 60 miles from the flume at the head of the canal. Originally carried principally by flume, the enormous expense of upkeep caused the company to substitute a gravel ditch and iron pipe

The company first constructed a ditch from the South Fork Mokelumne River to Mokelumne Hill, a distance of 16 miles. Much of the work was done by Chinese laborers, who comprised a large portion of the town’s population. The company built its own sawmill at Glencoe, near the present Three-Way Station. After reaching Mokelumne Hill, it was decided to extend the canal another 16 miles to Campo Seco, then a flourishing placer mining camp. Total costs were $95,000. Another agreement with Andrews and Cadwallader saw construction of a reservoir about one mile east of Campo Seco. The reservoir, now known as Watertown, was completed in October.

The ditch system consisted of a large storage reservoir in the mountains, distributing reservoirs, and a line or ditch and branches extending through Mokelumne Hill for town use, to Campo Seco and beyond, also serving intermediate places. The ditch enabled residents along the line to wash quartz and placer mines, to cultivate the soil by irrigation, or to run machinery by water power (Elliott 1885:77).

Saddled with immense debt due to the construction of the canal and its improvements, laterals, and extensions, the company was forced to seek a mortgage from Wade Hanson & Company, a Mokelumne Hill business firm. This company became insolvent and could not carry out the provisions of the lease, nor could the company pay for the Campo Seco extension and reservoir. Andrews and Cadwallader foreclosed on a judgment of $26,000.

The property was then sold to a group of Calaveras County men, many from Mokelumne Hill, who called their new company the Mokelumne, and Campo Seco Canal and Mining Company. By 1858 the company was assessed for “a ditch and flume, including branches about 106 miles long, commencing on the South Fork Mokelumne River about one-half mile below Conrad’s Bridge and terminating at Poverty Bar.” Title went to the new corporation in 1859, organized under the direction of Simon Foorman, company President.

Under Samuel L. Prindle, the new secretary and general manager, the company became very active and many improvements were completed. Water was conveyed as far west as Chili Camp and on to Valley Springs and Burson when the railroad was completed in the 1870s. One of the larger customers of the company was the Gwin Mine at Middle Bar, which used water from the ditch to operate the mine. A lateral was constructed to Central Hill, where Gourlay Reservoir was built.

In 1877, they purchased the A. W. Harris Sandy Gulch Ditch system, which conveyed water from the Middle Fork Mokelumne River. This water was then turned into the South Fork above the point of diversion and picked up in the ditch system. The company further consolidated county water structures through the purchase of Bingham Reservoir near Railroad Flat from David McCarty in 1879. This system ran water down the Calaveras River to divert it into the main canal near Rich Gulch.

The company continued to provide water for numerous purposes until Congress enacted the Sawyer Act in 1884, limiting hydraulic mining in the state. Many mines ceased operation and the demand for water decreased, as did revenue. With insufficient income to pay operating and maintenance expenses, the system became limited and in poor repair. By the early 1900s, the Campo Seco canal had been abandoned and carried water only as far as the Watertown Reservoir (Agostini 1904).

The company made application to the Railroad Commission to discontinue service as a public utility and during these proceedings the towns of Mokelumne Hill, San Andreas, and vicinities formed the Calaveras Public Utility District to ensure a continuous supple of water to their communities. The Mokelumne Hill Canal and Mining Company was reorganized as the Mokelumne River Water and Power Company. In 1934, the water rights were acquired by the Calaveras Public Utility District (CPUD) (Goffe 2006; Limbaugh 2004:147-148, 174). Bonds were issued, and with government assistance the property was purchased. A dam was constructed on the Middle Fork Mokelumne River, the ditch refurbished, new flumes installed, and water furnished to the inhabitants of the district (Smith 1959:1-2). Ditch water was discontinued to Mokelumne Hill in 1973, made obsolete by the installation of the CPUD pipeline bringing water to the area from Jeff Davis Reservoir (Las Calaveras, Volume XXXVI, No. 1:4). The water district, still in operation, converted some of the former ditch and flume system to pipelines in later years.

By Judith Marvin

References

Agostini, J. J. 1904. Official Map of Calaveras County. J.J. Agostini, San Andreas.

Elliott, Wallace W., 1885. Calaveras County, Illustrated and Described. W.W. Elliott, Oakland, California. Reprinted 1976 by the Calaveras County Historical Society, San Andreas.